Plunderphonia

[SeaLand, fony] 2001 / download

Until 1877, when the first sound recording was made, sound was a thing predicated on its own immediate disappearance; today it is increasingly an object that will outlast its makers and consumers. It declines to disappear, causing a great weigt of dead music to press upon the living. What to do with it? An organic response has been to recycle, an answer strenuously resisted by traditional music thinking. Yet, plagiarism, once rejected as insupportable, has today emerged both as a standard procedure and as a consciously self-reflexive activity, raising vexed debates about ownership, copyright, skill and cultural exhaustion. This essay attempts to sketch the history of plunderphonics and relate to it to the paradigm shift initiated by the advent of sound recording.

In this article, Cutler places sampling and “plunderphonics” in historical perspective, examining the ways in wich recording and musical technology have altered the very nature of music and musical practice. [Audio Culture. Readings in Modern Music, edited by Christoph cox and Daniel Warner]

by Chris Cutler [1994]

Introduction

[…]

John Oswald’s “Pretender” and other pieces – all originated from existing copyright recordings but employing radically different techniques – were included on an EP and later a CD, Plunderphonic (Oswald 1988). Both were given away free to radio stations and the press. None was sold. The liner note reads: ‘This disc may be reproduced but neither it, nor any reproductions of it are to be bought or sold. Copies are available only to public access and broadcast organizations, including libraries, radio or periodicals.’ The 12″ EP, consisting of four pieces – Pretender (Parson), Don’t (Presley), Spring (Stravinsky), Pocket (Basie) – was made between 1979 and 1988 and released in May 1988, with some support from the Arts Council of Canada. The CD, containing these and 20 other pieces was realized between 1979-89 and released on October 31st 1989 and was financed entirely by Oswald himself. Between Christmas Eve 1989 and the end of January 1990 all distribution ceased and all extant copies were destroyed. Of all the plundered artists it was Michael Jackson who pursued the CD to destruction. Curiously Jackson’s own plundering, for instance the one minute and six seconds of The Cleveland Symphony Orchestra’s recording of Beethoven’s Ninth which opens Jackson’s Will you be there? on the CD Dangerous, for which Jackson claims no less than six credits, including composer copyright (adding plagiarism to sound piracy), seems to have escaped his notice.

Pretender (Parton)

Don’t (Presley)

Necessity and choice (continued)

In 1980 I wrote that ‘From the moment of the first recording, the actual performances of musicians on the one hand, and all possible sound on the other, had become the proper matter of music creation.’ (Cutler 1991). I failed, however, to underline the consequence that ‘all sound’ has to include other people’s already recorded work; and that when all sound is just raw material, then recorded sound is always raw – even when it is cooked. This omission I wish now in part to redress.

Although recording offered all audible sound as material for musical organisation, art music composers were slow to exploit it, and remain so today. One reason is that the inherited paradigms though which art music continues to identify itself have not escaped their roots in notation, a system of mediation which determines both what musical material is available and what possible forms of organisation can be applied to it. The determination of material and organisation follows from the character of notation as a discontinuous system of instructions developed to model visually what we know as melody, harmony and rhythm represented by, and limited to, arrangements of fixed tones (quantised, mostly 12 to an octave) and fixed durations (of notes and silences). Notation does not merely quantise the material, reducing it to simple units but, constrained by writability, readability and playability, is able to encompass only a very limited degree of complexity within those units. In fact the whole edifice of western art music can be said, after a fashion, to be constructed upon and through notation1 which, amongst other things, creates ‘the composer’ who is thus constitutionally bound to it.

No wonder then that recording technology continues to cause such consternation. On the one hand it offers control of musical parameters beyond even the wildest dreams of the most radical mid-20th century composer; on the other it terminally threatens the deepest roots of the inherited art music paradigm, replacing notation with the direct transcription of performances and rendering the clear distinction between performance and composition null.

Perhaps this accounts for the curious relationship between the art music world and the new technology which has, from the start, been equivocal or at least highly qualified (Edgard Varese notably excepted). And it is why the story I shall have to tell is so full of tentative high art experiments that seem to die without issue and why, although many creative innovations in the new medium were indeed made on the fringes of high art, their adoption and subsequent extension has come typically through other, less ideologically intimidated (or less paradigmatically confused?) musical genres. Old art music paradigms and new technology are simply not able to fit together2.

For art music then, recording is inherently problematic – and surely plunderphonics is recording’s most troublesome child, breaking taboos art music hadn’t even imagined. For instance, while plagiarism was already strictly off limits (flaunting non-negotiable rules concerning originality, individuality and property rights), plunderphonics was proposing routinely to appropriate as its raw material not merely other people’s tunes or styles but finished recordings of them! It offered a medium in which, far from art music’s essential creation ex nihilo, the origination, guidance and confirmation of a sound object may be carried through by listening alone.

The new medium proposes, the old paradigms recoil. Yet I want to argue that it is precisely in this forbidden zone that much of what is genuinely new in the creative potential of new technology resides.In other words, the moral and legal boundaries which currently constitute important determinants in claims for musical legitimacy, impede and restrain some of the most exciting possibilities in the changed circumstances of the age of recording. History to date is clear on such conflicts: the old paradigms will give way. The question is – to what?

One of the conditions of a new art form is that it produce a metalanguage, a theory through which it can adequately be described. A new musical form will need such a theory. My sense is that Oswald’s Plunderphonic has brought at last into sharp relief many of the critical questions around which such a theory can be raised. For by coining the name, Oswald has identified and consolidated a musical practice which until now has been without focus. And like all such namings, it seems naturally to apply retrospectively, creating its own archaeology, precursors and origins.

Originality

Of all the processes and productions which have emerged from the new medium of recording, plunderphonics is the most consciously self-reflexive; it begins and ends only with recordings, with the already played. Thus, as I have remarked above, it cannot help but challenge our current understanding of originality, individuality and property rights. To the extent that sound recording as a medium negates that of notation and echoes in a transformed form that of biological memory, this should not be so surprising3. In ritual and folk musics, for instance, originality as we understand it would be a misunderstanding – or a transgression – since proper performance is repetition. Where personal contributions are made or expected, these must remain within clearly prescribed limits and iterate sanctioned and traditional forms.

Such musics have no place for genius, individuality or originality as we know them or for the institution of intellectual property. Yet these were precisely the concepts and values central to the formation of the discourse that identified the musical, intellectual and political revolution that lay the basis for what we now know as the classical tradition. Indeed they were held as marks of its superiority over earlier forms. Thus, far from describing hubris or transgression, originality and the individual voice became central criteria of value for a music whose future was to be marked by the restless and challenging pursuit of progress and innovation. Writing became essential, and not only for transmission. A score was an individual’s signature on a work. It also made unequivocal the author’s claim to the legal ownership of a sound blueprint. ‘Blueprint’ because a score is mute and others have to give it body, sound, and meaning. Moreover, notation established the difference and immortality of a work in the abstract, irrespective of its performance.

Copyright

The arrival of recording, however, made each performance of a score as permanent and fixed as the score itself. Copyright was no longer so simple4. When John Coltrane records (1961) My Favorite Things (Coltrane 1961), a great percentage of which contains no sequence of notes found in the written score, the assigning of the composing rights to Rogers and Hammerstein hardly recognizes the compositional work of Coltrane, Garrison, Tyner and Jones. A percentage can now be granted for an ‘arrangement’ but this doesn’t satisfy the creative input of such performers either. Likewise, when a collective improvisation is registered under the name, as often still occurs, of a bandleader, nothing is expressed by this except the power relations pertaining in the group. Only if it is registered in the names of all the participants, are collective creative energies honored – and historically, it took decades to get copyright bodies to recognize such ‘unscored’ works, and their status is still anomalous and poorly rated5. Still, this is an improvement: until the mid 1970s, in order to claim a composer’s copyright for an improvised or studio originated work, one had to produce some kind of score constructed from the record – a topsy-turvy practice in which the music created the composer. And to earn a royalty on a piece which started and ended with a copyright tune but had fifteen minutes of free improvising in the middle, a title or titles had to be given for the improvised parts or all the money would go to the author of the book ending melody. In other words, the response of copyright authorities to the new realities of recording was to cobble together piecemeal compromises in the hope that, between the copyrights held in the composition and the patent rights granted over a specific recording, most questions of assignment could be adjudicated – and violations identified and punished. No one wanted to address the fact that recording technology had called not merely the mechanics but the adequacy of the prevailing concept of copyright into question. It was Oswald, with the release of his not-for-sale EP and then CD who, by naming, theorizing and defending the use of ‘macrosamples’ and ‘electroquotes’, finally forced the issue. It was not so much that the principles and processes involved were without precedent but rather that through Oswald they were at last brought together in a focused and fully conscious form.

The immediate result was disproportionate industry pressure, threats and the forcible withdrawal from circulation and destruction of all extant copies. This despite the fact that the CD in question was arguably an original work (in the old paradigmatic sense), was not for sale (thereby not exploiting other people’s copyrights for gain) and was released precisely to raise the very questions which its suppression underlined but immediately stifled. Nevertheless, the genie was out of the bottle.

The fact is that, considered as raw material, a recorded sound is technically indiscriminate of source. All recorded sound, as recorded sound, is information of the same quality. A recording of a recording is just a recording. No more, no less. We have to start here. Only then can we begin to examine, as with photomontage (which takes as its strength of meaning the fact that a photograph of a photograph is – a photograph) how the message of the medium is qualified by a communicative intent that distorts its limits. Judgments about what is plagiarism and what is quotation, what is legitimate use and what, in fact if not law, is public domain material, cannot be answered by recourse to legislation derived from technologies that are unable even to comprehend such questions. When ‘the same thing’ is so different that it constitutes a new thing, it isn’t ‘the same thing’ anymore – even if, like Oswald’s hearing of the Dolly Parton record, it manifestly is the ‘same thing’ and no other. The key to this apparent paradox lies in the protean self-reflexivity of recording technology, allied with its elision of the acts of production and reproduction – both of which characteristics are incompatible with the old models, centered on notation, from which our current thinking derives, and which commercial copyright laws continue to reflect.

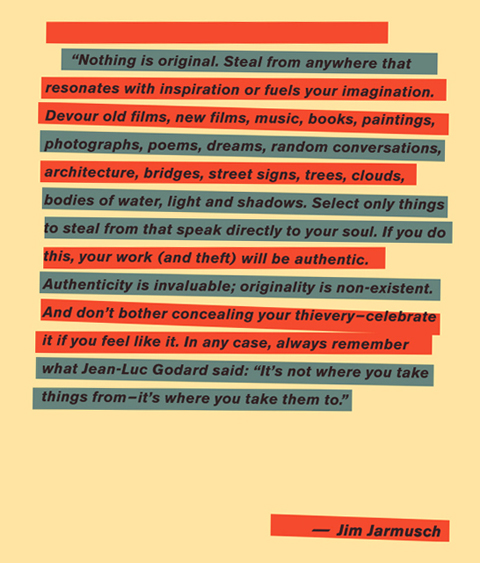

Thus plunderphonics as a practice radically undermines three of the central pillars of the art music paradigm: originality – it deals only with copies, individuality – it speaks only with the voice of others; and copyright – the breaching of which is a condition of its very existence.

Recording history: the gramophone

As an attribute unique to recording, the history of plunderphonics is in part the history of the self-realization of the recording process; its coming, so to speak, to consciousness.

[…]

The breakthrough for the record as a producing (as opposed to reproducing) medium came only in 1948 in the studios of French Radio with the birth of musique concrète. There were no technological advances to explain this breakthrough, only a thinking advance; the chance interpenetrations of time, place and problematic.

The first concrète pieces, performed at the Concert de Bruits in Paris by engineer/composer Pierre Schaeffer, were made by manipulating gramophone records in real time, employing techniques embedded in their physical form: varying the speed, reversing the direction of spin, making ‘closed grooves’ to create repeated ostinati etc.

[…]

Tape

[…]

Tape was not regularly employed in music until after the Second World War, when German improvements in recording and playback quality and in stable magnetic tape technology were generally adopted throughout the world. Within five years tape had become standard in all professional recording applications.

The vinyl disc meanwhile held its place as the principle commercial playback medium and thus the ubiquitous public source of recorded sound. This division between the professionally productive and socially reproductive media was to have important consequences, since it was on the gramophone record that music appeared in its public, most evocative form; and when resonant cultural fragments began to be taken into living sound art, it was naturally from records, from the ‘real’ artefacts that bricoleurs would draw.

[…]

High and Low

Popular musics got off to a slow start with sound piracy. Nevertheless they soon proved far more able to explore its inherent possibilities than art musics, which even after fifty years of sporadic experiment remained unable rigorously so to do.

[…]

A record makes all musics equally accessible – in every sense. No special clothes are needed, no expensive tickets need be bought, no travel is necessary, one need belong to no special interest or social group, nor be in a special place at a special time. Indeed, from the moment recordings existed, a new kind of ‘past’ and ‘present’ were born – both immediately available on demand. Time and space are homogenized in the home loudspeaker or the headphone and the pop CD costs the same as the classical CD and probably comes from the same shop. All commodities are equal.

For young musicians growing up in the electric recording age, immersed in this shoreless sea of available sound, electronics, Maltese folk music, bebop, rhythm and blues, show tunes, film soundtracks and the latest top ten hit were all equally on tap. Tastes, interests, studies could be nourished at the pace and following the desire of the listener. Sounds, techniques and styles could flit across genres as fast as you could change a record, tune a dial or analyze and imitate what you heard. A kind of sound intoxication arose. Certainly it was the ideas and applications encountered in recorded music of all types which led a significant fringe of the teenage generation of the late 1960s into experiments with sound, stylistic bricolage, importations, the use of noise, electronics, ‘inappropriate’ instruments and – crucially – recording techniques10. The influence of art music and especially the work of Varese, Schaeffer, Stockhausen and others cannot be overestimated in this context and, more than anything, it would be the crossplay between high and low art that would feature increasingly as a vital factor in the development of much innovative music. In plunderphonics too, the leakages – or maybe simply synchronicities – between productions in what were once easily demarcated as belonging in high or low art discourses, are blatant. Indeed, in more and more applications, the distinction is meaningless and impossible to draw.

[…]

The world of low art had few such scruples: indeed, in a profound sense plundering was endemic to it – in the ‘folk’ practices of copying and covering for instance (few people played original compositions), or in the use of public domain forms and genres as vessels for expressive variation (the blues form, sets of standard chord progressions and so on). The twentieth-century art kind of originality and novelty simply was not an issue here. Moreover, in the ‘hands on’, low expectation, terra nova world of rock, musicians were happy to make fools of themselves ‘rediscovering America’ the hard way.

What I find especially instructive was how, in a sound world principally mediated by recording, high and low art worlds increasingly appropriated from one another. And how problems that were glossed over when art was art and there was no genre confusion (like Tenney’s appropriation of copyright, but lowbrow, recordings) suddenly threatened to become dangerously problematic when genres blurred and both plunder and original began to operate in the same disputed (art/commercial) space.

[…]

Sampling and scratching

Although there were some notable experiments and a few successful productions, tape and disc technologies made plundering difficult and time consuming and thus suitable only for specific applications. What brought plundering to the centre of mass consumption low art music was a new technology that made sound piracy so easy that it didn’t make sense not to do it. This development was digital sampling, launched affordably by Ensoniq in the mid-1980s. Digital sampling is a purely electronic digital recording system which takes samples or ‘vertical slices’ of sound and converts them into binary information, into data, which tells a sound producing system how to reconstruct, rather than reproduce it. Instantly.

At a fast enough sampling rate the detailed contours of a sound can be so minutely traced that playback quality is compatible with any analogue recording system. The revolutionary power associated with a digital system is that the sound when stored consists of information in a form that can be transformed, edited or rewritten electronically, without ‘doing’ anything to any actual analogue recording but only to a code. This really is a kind of a writing. When it is stored, modified or reproduced, no grooves, magnetized traces or any other contiguous imprint link the sound to its means of storage (by imprint I mean as when an object is pressed into soft wax and leaves its analogue trace). It is stored rather as discrete data, which act as instructions for the eventual reconstruction of a sound (as a visual object when electronically scanned is translated only into a binary code). Digital sampling allows any recorded sound to be linked to a keyboard or to a Midi trigger and, using electronic tools (computer software), to be stretched, visualized on screen as waveforms and rewritten or edited with keys or a light pencil. All and any parameters can be modified and any existing electronic processing applied. Only at the end of all these processes will an audible sound be recreated. This may then be listened to and, if it is not what is wanted, reworked until it is and only then saved. It means that a work like Cage’s four minute long Williams Mix (the first tape collage made in America) which took a year to cut together, could now be programmed and executed quite quickly using only a domestic computer.

The mass application is even more basic. It simply puts any sound it records – or which has been recorded and stored as software – on a normal keyboard, pitched according to the key touched. The user can record, model and assign to the keys any sounds at all. At last here is a musical instrument which is a recording device and a performing instrument – whose voice is simply the control and modulation of recordings. How could this technology not give the green light to plundering? It was so simple. No expertise was needed, just a user friendly keyboard, some stuff to sample (records and CDs are easy – and right there at home), and plenty of time to try things out. Producing could be no more than critical consuming; an empirical activity of Pick’n’Mix. Nor was that all. Sampling was introduced into a musical climate where in low art plundering was already deeply established in the form of ‘scratching’ – which in its turn echoed in a radically sophisticated form the disc manipulation techniques innovated in high culture by Hindemith and Koch, Milhaud, Varese, Honegger, Kagel, Cary, Schaeffer et al, but now guided by a wholly different aesthetic.

From scratch

The term ‘scratching’ was coined to describe the practice of the realtime manipulation of 12 inch discs on highly adapted turntables.

[…]

“Two manual decks and a rhythm box is all you need. Get a bunch of good rhythm records, choose your favorite parts and groove along with the rhythm machine. Using your hands, scratch the record by repeating the grooves you dig so much. Fade one record into the other and keep that rhythm box going. Now start talking and singing over the record with your own microphone. Now you’re making your own music out of other people’s records. That’s what scratching is”. (McLaren (1982)

Oswald plays records

Curiously, the apotheosis of the record as an instrument – as the raw material of a new creation – occurred just as the gramophone record itself was becoming obsolete and when a new technology that would surpass the wildest ambitions of any scratcher, acousmaticist, tape composer or sound organizer was sweeping all earlier record/playback production systems before it. Sampling, far from destroying disc manipulation, seems to have breathed new life into it. Turntable techniques live on in live House and Techno.

[…]

It is almost as if sampling had recreated the gramophone record as a craft instrument, an analogue, expressive voice, made authentic by nostalgia. Obsolescence empowers a new mythology for the old phonograph, completing the circle from passive repeater to creative producer, from dead mechanism to expressive voice, from the death of performance to its guarantee. It is precisely the authenticity of the 12 inch disc that keeps it in manufacture; it has become anachronistically indispensable.

[…]

More dead than quick

What is essential – and new – is that by far the largest part of the music that we hear is recorded music, live music making up only a small percentage of our total listening. Moreover, recording is now the primary medium through which musical ideas and inspiration spread (this says nothing about quality, it is merely a quantitative fact). For example, one of the gravitational centres of improvisation – which is in every respect the antithesis of fixed sound or notated music – is its relation to recorded sound, including recordings of itself or of other improvisations. This performance-recording loop winds through the rise of jazz as a mass culture music, through rock experiments and on to the most abstract noise productions of today. Whatever living music does, chances are that the results will be recorded – and this will be their immortality. In the new situation, it is only what is not recorded that belongs to its participants while what is recorded is placed inevitably in the public domain.

Moreover, as noted earlier, recorded music leaves its genre community and enters the universe of recordings. As such the mutual interactions between composers, performers and recordings refer back to sound and structure and not to particular music communities. Leakage, seepage, adoption, osmosis, abstraction, contagion: these describe the life of sound work today. They account for the general aesthetic convergence at the fringes of genres once mutually exclusive – and across the gulf of high and low art. There is a whole range of sound work now about which it simply makes no sense to speak in terms of high or low, art or popular, indeed where the two interpenetrate so deeply that to attempt to discriminate between them is to fail to understand the sound revolution which has been effected through the medium of sound recording.

Plunderphonics addresses precisely this realm of the recorded. It treats of the point where both public domain and contemporary sound world meet the transformational and organizational aspects of recording technology; where listening and production, criticism and creation elide. It is also where copyright law from another age can’t follow where – as Oswald himself remarked – ‘If creativity is a field, copyright is the fence’13.

Pop eats itself

First, and most obvious, is the widespread plundering of records for samples that are recycled on Hip Hop, House and Techno records in particular, but increasingly on pop records in general. This means that drum parts, bass parts (often loops of a particular bar), horn parts, all manner of details (James Brown whoops etc.) will be dubbed off records and built up layer by layer into a new piece.

[…]

Rhythms and tempi can be adjusted and synchronized, pitches altered, dynamic shape rewritten and so on. Selections sampled may be traceable or untraceable, it need not matter. Reference is not the aim so much as a kind of creative consumerism, a bricolage assembly from parts. Rather than start with instruments or a score, you start with a large record and CD collection and then copy, manipulate and laminate.

Moral and copyright arguments rage around this. Following several copyright infringement cases, bigger studios employ someone to note all samples and to register and credit all composers, artists and original recording owners. ‘Sampling licences’ are negotiated and paid for. This is hugely time consuming and slightly ridiculous and really not an option for amateurs and small fish. Oswald’s Plexure, for instance, has so many tiny cuts and samples on it that, not only are their identities impossible to register by listening, but compiling credit data would be like assembling a telephone directory for a medium sized town. Finding, applying, accounting and paying the 4000-plus copyright and patent holders would likewise be a full time occupation, effectively impossible. Therefore such works simply could not exist. We have to address the question whether this is what we really want.

For now I am more interested in the way pop really starts to eat itself. Here together are cannibalism, laziness and the feeling that everything has already been originated, so that it is enough now endlessly to reinterpret and rearrange it all. The old idea of originality in production gives way to another (if to one at all) of originality in consumption, in hearing.

[…]

The Issue

What is the issue? Is it whether sound can be copyrighted or snatches of a performance? If so, where do we draw the line – at length or reconcilability? Or does mass produced, mass disseminated music have a kind of folk status? Is it so ubiquitous and so involuntary (you have to be immersed in it much of your waking time) that it falls legitimately into the category of ‘public domain’? Since violent action (destruction of works, legal prohibition, litigation and distrait) have been applied by one side of the argument, these are questions we cannot avoid.

A BRIEF REVIEW OF APPLICATIONS

A: There It Is

There are cases such as that of Cage, in Imaginary Landscapes 2 and 4, where materials are all derived directly from records or radio and subjected to various manipulations. Though there are copyright implications, the practice implies that music picked randomly ‘out of the air’ is simply there. Most of Cage’s work is more a kind of listening than of producing.

B: Partial Importations

An example of partial importation is My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts (Byrne and Eno) and the work of Italians Roberto Musci and Giovanni Venosta. In both cases recordings of ethnic music are used as important voices, the rest of the material being constructed around them. The same might be done with whale songs, sound effects records and so on; I detect political implications in the absence of copyright problems on such recordings. At least, it is far from obvious to me why an appeal to public domain status should be any more or less valid for ‘ethnic’ music than it is for most pop – or any other recorded music.

C: Total Importation

This might rather be thought of as interpretation or re-hearing of existing recordings. Here we are in the territory of Tenney, Trythall, The Residents, Marclay and quintessentially, of plunderphonic pioneer John Oswald. Existing recordings are not randomly or instrumentally incorporated so much as they become the simultaneous subject and object of a creative work. Current copyright law is unable to distinguish between a plagiarized and a new work in such cases, since its concerns are still drawn from old pen and paper paradigms. In the visual arts Duchamp with readymades, Warhol with soupcans and brillo boxes, Lichtenstein with cartoons and Sherry Levine with re-photographed ‘famous’ photographs are only some of the many who have, one way or another, broached the primary artistic question of ‘originality’, which Oswald too can’t help but raise.

D: Sources Irrelevant

This is where recognition of parts plundered is not necessary or important. There is no self-reflexivity involved; sound may be drawn as if ‘out of nothing’, bent to new purposes or simply used as raw material. Also within this category falls the whole mundane universe of sampling or stealing ‘sounds’: drum sounds (not parts), guitar chords, riffs, vocal interjections etc., sometimes creatively used but more often simply a way of saving time and money. Why spend hours creating or copying a sound when you can snatch it straight off a CD and get it into your own sampler-sequencer?

E: Sources Untraceable

These are manipulations which take the sounds plundered and stretch and treat them so radically that it is impossible to divine their source at all. Techniques like this are used in electronic, concrete, acousmatic, radiophonic, film and other abstract sound productions. Within this use lies a whole universe of viewpoints. For instance, the positive exploration of new worlds of sound and new possibilities of aestheticisation – or the idea that there is no need to originate any more, since what is already there offers such endless possibilities – or the expression of an implied helplessness in the face of contemporary conditions, namely, everything that can be done has been done and we can only rearrange the pieces. This is a field where what may seem to be quite similar procedures may express such wildly different understandings as a hopeless tinkering amidst the ruins or a celebration of the infinitude of the infinitesimal.

Final comments

Several currents run together here. There is the technological aspect: plundering is impossible in the absence of sound recording. There is the cultural aspect: since the turn of the century the importation of readymade materials into artworks has been a common practice, and one which has accumulated eloquence and significance. The re-seeing or re-hearing of familiar material is a well established practice and, in high art at least, accusations of plagiarism are seldom raised. More to the point, the two-way traffic between high and low art (each borrowing and quoting from the other) has proceeded apace. Today it is often impossible to draw a clear line between them – witness certain advertisements, Philip Glass, Jeff Koons, New York subway graffiti.

It seems inevitable that in such a climate the applications of a recording technology that gives instant playback, transposition and processing facilities will not be intimidated by the old proscriptions of plagiarism or the ideal of originality. What is lacking now is a discourse under which the new practices can be discussed and adjudicated. The old values and paradigms of property and copyright, skill, originality, harmonic logic, design and so forth are simply not adequate to the task. Until we are able to give a good account of what is being done, how to think and speak about it, it will remain impossible to adjudicate between legitimate and illegitimate works and applications. Meanwhile outrages such as that perpetrated on John Oswald will continue unchecked.

Posted in academia, copy++ on August 9th, 2009 by fresh good minimal | 24 Comments

gmail

gmail com

com